One of the problems of having two thousand years of Christianity behind us is that we have forgotten our roots. Jesus was Jewish, as were most people in the first generation church. Most of what Jesus said was intended to be understood by his fellow Jews. He was in constant dialogue with Judaism—and so was the Apostle Paul, who wrote more books in the Christian Bible than anybody else.

We’ve lost that, of course. We seldom ask how Jesus’ words and actions connected to his religion. And we often assume the worst when Paul talks about Christianity’s relationship to Judaism. And in no area is this misunderstanding worse than when we talk about the Law of God. Both Jesus and Paul engage with it constantly, and a good place for us to begin looking at this relationship is today’s scripture—the one where Jesus says that his yoke is easy and his burden is light.

We know what Joseph—Jesus’ earthly father—did for a living: he was a carpenter. In Matthew 13, when Jesus returns to his hometown and tries to share his teachings, that’s their reaction: Who is this guy? Isn’t this the carpenter’s son? When Mark (chapter 6) records this, the people connect Jesus more directly to woodworking: Isn’t this guy just a carpenter? they ask. And so, if we wonder what Jesus was doing for thirty years before he began his ministry, there’s our answer. He was a carpenter.

The scriptures don’t tell us any stories about what Jesus did as a carpenter, but one of the things people might well have needed from him and Joseph was a wooden farm implement known as a yoke. We don’t use this word a lot in our culture: Not only are most of us at least a generation or two removed from the farm, but in our day and age, the need for yokes has largely been replaced by tractors.

But the word yoke would at one time have been one of the most oft-used and necessary words in the English language. And not just English, but just about any language that was used by a people who depended on agriculture. In fact, the word yoke is so historically important, that it’s one of the words that has changed the least. We can still see and hear the similarities between the English word for yoke and the German and Scandinavian and Spanish and Italian and even the Lithuanian words meaning the same thing.

My grandmother was born in 1912 in northeastern Kentucky. There were certainly cars in her day, and probably even tractors. But of course, tractors were not in use in rural Appalachia until much later. And so she was acquainted with yokes. She even had one that she’d kept as decoration. It was a “single tree”—a single wooden bar that was supposed to be attached to a pair of animals (probably mules) so that they could be guided to pull a plow. There’s a hotel chain called DoubleTree, which uses two trees as its logo. But the original term “double tree” referred to a more complex yoke, used for an entire team of horses.

But yokes in Jesus’ day were usually for oxen, and they were made to rest more directly on the animals’ shoulders. And so a certain amount of skill was needed to make yokes that would not irritate. The better the yoke, the more productive the ox. So I think we are probably safe in assuming that, though Jesus was no farmer, he understood one of the most important farm implements: the yoke.

And his listeners would’ve understood, too. They were all either on a farm or depended much more directly on farmers than most of us do. And yoke wasn’t just a literal farm implement in their minds. It was also a metaphor that they heard often. The yoke was a metaphor for both slavery and for God’s Law.

Central to Jewish identity, then as now, was the fact that their ancestors had been slaves in Egypt. But God had delivered them and replaced the unbearable yoke of slavery with the gentle yoke of the Law. And that’s how the law was supposed to be understood. It was what connected them to their people and it was what guided them through life.

The opening words of the entire Book of Psalms gives us an idea of how the Jewish people viewed the Law:

We’ve lost that, of course. We seldom ask how Jesus’ words and actions connected to his religion. And we often assume the worst when Paul talks about Christianity’s relationship to Judaism. And in no area is this misunderstanding worse than when we talk about the Law of God. Both Jesus and Paul engage with it constantly, and a good place for us to begin looking at this relationship is today’s scripture—the one where Jesus says that his yoke is easy and his burden is light.

We know what Joseph—Jesus’ earthly father—did for a living: he was a carpenter. In Matthew 13, when Jesus returns to his hometown and tries to share his teachings, that’s their reaction: Who is this guy? Isn’t this the carpenter’s son? When Mark (chapter 6) records this, the people connect Jesus more directly to woodworking: Isn’t this guy just a carpenter? they ask. And so, if we wonder what Jesus was doing for thirty years before he began his ministry, there’s our answer. He was a carpenter.

The scriptures don’t tell us any stories about what Jesus did as a carpenter, but one of the things people might well have needed from him and Joseph was a wooden farm implement known as a yoke. We don’t use this word a lot in our culture: Not only are most of us at least a generation or two removed from the farm, but in our day and age, the need for yokes has largely been replaced by tractors.

But the word yoke would at one time have been one of the most oft-used and necessary words in the English language. And not just English, but just about any language that was used by a people who depended on agriculture. In fact, the word yoke is so historically important, that it’s one of the words that has changed the least. We can still see and hear the similarities between the English word for yoke and the German and Scandinavian and Spanish and Italian and even the Lithuanian words meaning the same thing.

My grandmother was born in 1912 in northeastern Kentucky. There were certainly cars in her day, and probably even tractors. But of course, tractors were not in use in rural Appalachia until much later. And so she was acquainted with yokes. She even had one that she’d kept as decoration. It was a “single tree”—a single wooden bar that was supposed to be attached to a pair of animals (probably mules) so that they could be guided to pull a plow. There’s a hotel chain called DoubleTree, which uses two trees as its logo. But the original term “double tree” referred to a more complex yoke, used for an entire team of horses.

But yokes in Jesus’ day were usually for oxen, and they were made to rest more directly on the animals’ shoulders. And so a certain amount of skill was needed to make yokes that would not irritate. The better the yoke, the more productive the ox. So I think we are probably safe in assuming that, though Jesus was no farmer, he understood one of the most important farm implements: the yoke.

And his listeners would’ve understood, too. They were all either on a farm or depended much more directly on farmers than most of us do. And yoke wasn’t just a literal farm implement in their minds. It was also a metaphor that they heard often. The yoke was a metaphor for both slavery and for God’s Law.

Central to Jewish identity, then as now, was the fact that their ancestors had been slaves in Egypt. But God had delivered them and replaced the unbearable yoke of slavery with the gentle yoke of the Law. And that’s how the law was supposed to be understood. It was what connected them to their people and it was what guided them through life.

The opening words of the entire Book of Psalms gives us an idea of how the Jewish people viewed the Law:

Happy are those who do not follow the advice of the wicked, or take the path that sinners tread, or sit in the seat of scoffers; but their delight is in the law of the Lord, and on his law they meditate day and night.

—Ps. 1:1-2

Here we see the difference between taking bad advice, going off in the wrong direction, and having a negative attitude all compared and contrasted to prioritizing God’s Law and always thinking about what God’s Law means. Please note that God’s Law isn’t seen here as some set of rules to be followed mindlessly, but as a way of life to be engaged in.

And so, to throw off the yoke of slavery and taking on the yoke of God’s Law was seen as a very positive thing. But there are always those who can manipulate a good thing and make it very negative. Such people existed in Jesus’ day, and they cornered the market on meditating on God’s Law. No longer were people to be in dialogue with it on their own. No, they were to follow others’ hard-and-fast rules on what to do and what not to do and when to do what.

But Jesus’ message was to announce the coming of the Kingdom of God. This was the day that the Prophet Jeremiah [see Jer. 31:31-34] had promised when God would make a new covenant with God’s people, when the Law would be written in their hearts, when all would know God from within. This is the gentle yoke Jesus invited people to take on. And here’s how I think the master carpenter intended us to understand that his yoke is easy and his burden is light.

First of all, his was a yoke of humility. No more striving to impress—either with knowledge or status or possessions. It is enough to know God, to be who God made us to be, and to be grateful for what we have. This is not the same as doing nothing, because no matter how old we are, we all need to grow into ourselves and continually seek places where we can serve and people we can be of service to. Jesus lived and died in service of others. And if we take his yoke upon us, then so will we.

And so Jesus’ yoke was also a yoke of integrity. If you listen to what Jesus had to say throughout his ministry, this is a message we hear again and again—especially in the Sermon on the Mount. To take on the yoke of God’s Law does not just mean outward obedience. That would make the Kingdom of God some sort of totalitarian regime. The yoke that Jesus offers is one in which thoughts and words and deeds are one. We don’t say what we don’t mean, and we don’t practice what we don’t preach.

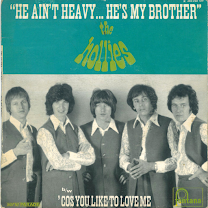

And finally, Jesus’ yoke was the yoke of love. I don’t know if younger generations know this song or not, but people my age and older certainly do. Even if you’d never listened to the words of the song, the title said it all: He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother. That phrase was already well-used by the time that song was written in 1969, but it can be traced all the way back to 1884 when it was used in a Scottish book about Jesus’ parables.

This book contained the story of a very small girl carrying a hefty baby boy. Someone stopped and asked her if she was getting tired carrying him. And she answered (of course), “He’s not heavy, he’s my brother!” The point being that when we assume the yoke of Christ, nothing is a burden if we take it on out of love for God or love for our neighbor.

In the end, we all need to face up to the fact that we are none of us completely free. We all take on burdens—sometimes fully knowing what we’re doing, but often not realizing the burden we’re assuming until later (if at all). Things we think we enjoy might become an addiction. Things we do in secret can become an unbearable weight. So much energy can be spent on having the best or being number one that we have no time left to live our lives.

And then there is the burden of taking on Christ. It is the burden of accepting second place—or even last place. It is the burden of accepting—and being—ourselves. It is the burden of loving others. Compared to the yoke of pride or the yoke of lies or the yoke of hatred and vengeance, the yoke of Jesus really is easy and his burden is truly light. His words, “Come to me, all of you who are weary and carry heavy burdens,” weren’t just addressed to the crowds of twenty centuries ago. They’re meant for us as well. So come to him and take on his yoke, for it is easier than the one we’re already carrying, and compared to the burdens of the world, his is indeed light.

—©2023 Sam Greening